As one ventures further towards the northern-eastern reaches of Australia, not only does the sugarcane start to dominate the landscape, so do the squashed Cane Toads that litter the roads !!!

As one ventures further towards the northern-eastern reaches of Australia, not only does the sugarcane start to dominate the landscape, so do the squashed Cane Toads that litter the roads !!!

Estimates suggest that over 200 tons of cane toads are sploshed onto Queensland’s roads in just one year !

Caution: Cane Toads (Rhinella marina) are venomous !!!

The Toxins

The Cane Toad is particularly dangerous to our pets and native fauna – records of humans death are conflicting, from none to a few . . . They are equipped with specialised glands (parotoid glands) that secret a venomous, milky, potentially fatal slime when threatened. Toxins are also present in their body tissues, toad eggs and tadpoles. There are mixed reports as to their ability to squirt their poison – some say not – others that they can emit a fine spray which travels a short distance – and, the most dramatic reports suggest that they can squirt it up to a distance of 2 m !! In any case, caution is advised . . .

Cane Toads are poisonous at every life stage of their life cycle.

Their venom is toxic and can kill. Domestic dogs can die within 15 minutes of ingesting a Cane Toad. The toxin is absorbed through the body tissues in the eyes, nose and mouth. A direct hit to the eye can cause immediate temporary blindness.

The venom of the Cane Toad is corrosive and contains a mix of, Bufotenin, is a toxic Alkaloid (examples of alkaloids include morphine, strychnine, quinine, nicotine, etc.) which is known for its psychedelic effects, and, cardiac glycosides which affect the heart, causing it to race (ventricular tachycardia), spasm (ventricular fibrillation) and ultimately arrest (the heart stops → death).

Coupled with the corrosive nature and toxicity of the venom, it is also very sticky, making it difficult to remove thus extending the time of exposure. Depending on the amount of toxin absorbed, symptoms may include: drooling / frothing at the mouth, shaking head, vomiting / dry reaching, weakness / muscle tremors, difficulty breathing, blue gums, seizures and possibly even death.

Contact your Vet immediately.

How the Cane Toad came to be in Australia

Toads are not native to Australia.

As the name would imply, the Cane Toad is associated with sugarcane. They were introduced into Australia to combat the native Australian cane beetle, Dermolepida albohirtum, which was destroying the introduced sugarcane crops. The adult beetles eat the leaves, and, the hatching larvae underground, eat the roots. The root damage results in reduced growth, lodging (when the root mass can no longer support the plant & partially tips out of the ground), stool tipping (when there is insufficient root mass remaining to anchor the stool into the ground), and sometimes even death of the plant. Damaged stools are often lost at harvest or fail to ratoon.

Cane Beetles

The Greyback cane beetles are a scarab beetle, growing up to 35 mm in length. They have grey wing covers coated by scales which develop dark brown patches as they wear off.

Their annual cycles is largely as follows:

The beetles generally emerge from the underground after good rains – usually between the months of October to February.

They fly after dark to feed on trees, including figs, wattles, eucalypts and palms. The females feed for up to 2 weeks before laying eggs when they return to the soil, prior to the break of day, at which time they lay some 20 to 30 eggs in one clutch, some 20 – 45 cm deep into the soil. They can lay up to 3 clutches of eggs.

The cane grubs hatch about 2 weeks later. The larvae feeds for 4 weeks or so on organic matter and roots – usually close to the surface.

They then gather under the cane stools and feed on the roots for the next 5 weeks.

During February to May they grow rapidly, feeding heavily on the roots and stools of the sugarcane – the time of the most damage to the crop.

The fully fed grubs then burrow down and form pupation chambers in the soil – turning into pupae for the months of July to October.

The beetles then emerge but remain in their chambers until suitable weather conditions trigger their emergence from the underground, and, the annual cycle begins again . . .

The miracle cure for this damaging beetle was believed to be the cane toad.

The Arrival of the Cane Toad in Australia

The first cane toads were brought into Queensland in 1935, by Reginald Mungomery, an entomologist with Queensland’s Bureau of Sugar Experiment Stations posted in Meringa, near Cairns.

102 South American Cane Toads – 51 females and 51 males – arrived in Cairns, from Hawaii, on the 22nd June 22 1935.

They were first taken to a facility to ensure they would cope with the transition to a new country.

The alarm bells should have been ringing when the Cane Toads began reproducing at an alarming rate within the first weeks of their arrival. They began laying eggs within one week – the eggs to began to hatch within 3 days . . .

Within weeks the Cane Toad numbers had increased into the thousands !!! – which were then realeased into the Mulgrave River near Gordonvale, Queensland in the August of 1935.

By the March of 1937, further releases totalling some 62,000 toadlets were realeased in areas around Cairns, Innisfail, Ingham, Ayr, Mackay and Bundaberg.

.

Today, estimates suggest that over 1.5 billion Cane Toads occupy some 100,000 sq km of Australia.

Their life expectancy is between 10 to 15 years in the wild – with reports of up to 35 years of age in captivity !!

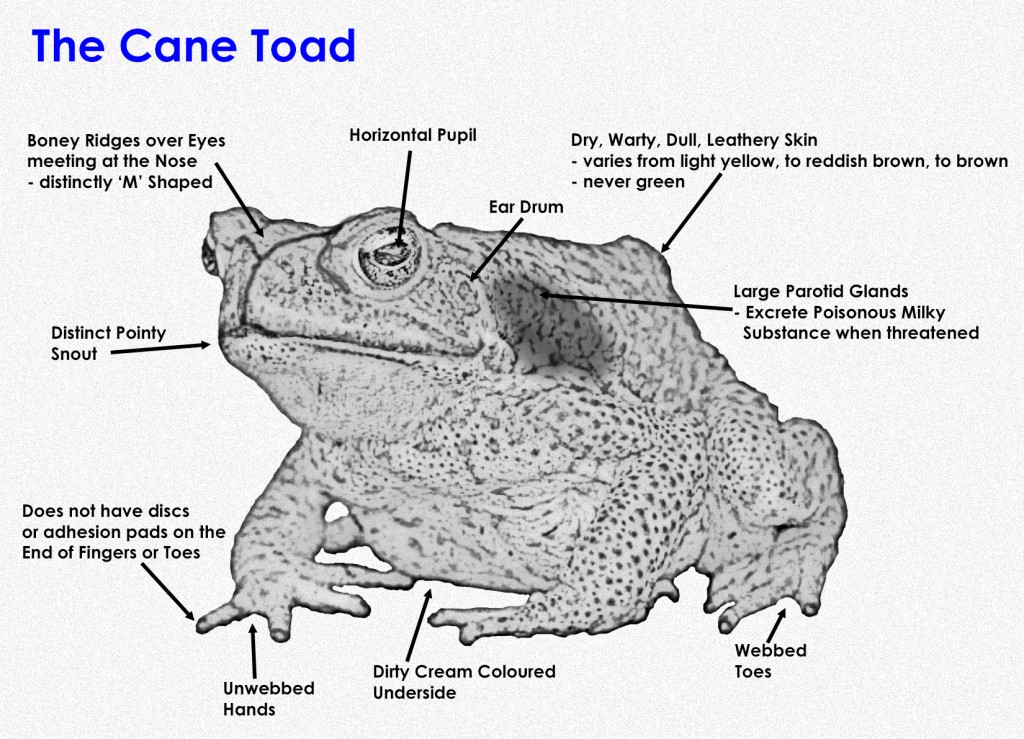

Cane Toads are large, stocky, heavily built amphibians of between 10 – 15 cm in length; with dry, warty skin that ranges from olive or reddish brown to a grey or even yellowish colour. The females are larger than the males; and the males are much ‘wartier’ than their female counterparts.

Reports of huge Cane Toads suggest that they can grow up to lengths of up to 23 cm – weighing in at a massive 1.8 kg !!!

The Cane Toad sits quite upright and moves in short rapid hops. They are generally slow movers and do not jump very high.

Their lack of agility meant that they could not reach the beetles they were introduced to eat !!! – and hence, they were totally ineffective in saving the sugarcane crops . . .

The Australian Invasion

Meanwhile, their toxic venom, adaptability, and incredible reproductive skills reeked havoc on Australia’s wildlife and habitats.

Females can lay up to 35,000 eggs per clutch which likens to a double strand of eggs contained in a long strand of gelatinous jelly – spawning multiple times in a year. Cane Toad tadpoles look quite different to our native species of frog, as they are jet black with big nostrils, and a wider body across the gills.

The Cane Toad venom is deadly to almost all native Australian animals. They have had a direct impact on the reduction of populations of dingoes, crocodiles, northern quolls, crows, kookaburras, goannas, frill‐necked lizards, frogs, snakes, native snails and leeches.

Over time, many species have learned not to mess with a Cane Toad, and others, how to avoid their venom resulting in some recovering populations. Interestingly, the Ibis, Torresian Crow, Snapping Turtle, Freshwater Snake, Saltwater Crocodile and Water Rat can eat cane toads and survive.

Cane Toads are carnivorous. Their diet consists mainly of insects, however, they are opportunistic feeders and will also eat small vertebrates, other Cane Toads, and even dog food. They are generally nocturnal and are frequently found around outdoor lights that attract nocturnal insects.

The colossal spread of the Cane Toad in Australia is largely due to their evolutionary skills.

The Cane Toads on the frontline are the fastest and strongest of the toads, resulting in their offspring becoming increasingly robust. Hence, the swift evolution is producing longer legs, bigger bodies, and a more straight-line migration pattern than that of their ancestors – the slow ones are simply get left behind. They are also found to be spreading ‘accidentily’ by hitching a ride on cars, trucks and trains – thereby finding a new home . . .

The invasion front initially moved approximately 10 km per year. By 1945 they had reached Brisbane, Byron Bay by 1965, the Northern Territory by 1984, and, Western Australia by 2009. The invasion front is now estimated to be moving at a rate of between 40 to 60 km per year.

Cane Toads are also adapting to dry climates – supported by the fact that they are now well established in Longreach, Queensland, as well as desert regions along the Victoria River in the Northern Territory. They are learning to sleep at night or by day, helping them cope with hotter and dryer conditions . . .

View other important events in Queensland’s History . . .