‘The Rip’ is defined as the narrow passage that joins Bass Strait to Port Phillip Bay in Victoria, Australia.

The notorious and infamous waters of ‘The Rip’ are known to mariners around the world and still impart dread into captains and their crews . . .

In 1802 the earliest explorers, who within 10 weeks of each other, dared enter this treacherous stretch of water were Lieutenant John Murray and Matthew Flinders. They both documented this unusual and extremely dangerous phenomenon.

Acting Surveyor General of New South Wales, C Grimes noted on his map of 1803 ” . . . Strong ripplings of tide in the entrance like breakers . . . “

‘The Rip’ is delineated by: Port Phillip Heads (being Point Lonsdale and Point Nepean) across to Shortland’s Bluff (just south of Queenscliff).

” . . . Grimes made the first survey and prepared the first chart of the Bay; but in 1836, Captain Hobson, whilst on a trip from Sydney to Melbourne in H.M.S. “Rattlesnake,” instituted a more thorough examination.

It may be as well to state here that the whole of the harbour was named Port Phillip, after Captain Arthur Phillip, the first Governor of New South Wales; and its upper portion or head Hobson’s Bay, after the Captain Hobson just mentioned. Two well known localities at the Heads were designated Points Nepean and Lonsdale, the first in compliment to Sir Evan Nepean, of the Admiralty, and the other to William Lonsdale, the first Police Magistrate and Commandant of Port Phillip. The nomenclature of Queenscliff has undergone some amusing nominal alterations. It was first called Whale’s Point by Captain Woodriff Commander of the ” Calcutta,” the principal ship of the Collins Convict Expedition of 1803, in consequence of its formation resembling the head of a whale. It was also known as Shortland’s Bluff, after Lieutenant John Shortland, a naval officer, who in 1788 accompanied “the first Fleet” to Sydney as Government Agent. Sorrento, when it formed the infant penal settlement of Collins, was officially known as Sullivan Bay and Sullivan Camp, after Mr. John Sullivan, an Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies . . . “

Source: Excerpt – ‘The Chronicles of Early Melbourne – 1835 to 1851 – Vol I’ – by Garryowen – published 1888

Though the physical and visible structures of each side of Port Phillip Heads measure approximately 3.5 km between them, the irregular, submerged, rocky outcrops that line both sides of the Heads reduce that space to a navigable waterway of only around 1 km in width – dependent on the vessel. Tides flow in and out of the narrow entrance at approximately 9 to 13 km per hr – often meeting in the middle. ‘The Rip’ is flanked by ‘Lonsdale Reef’ to the west and the ‘Point Nepean Reef’ to the east – the main shipping channel itself, being a depth in the vicinity of some 30 m, noting that the shallowest part of the channel once measured approximately 9 m in depth. Blasting over a period in excess of a century has increased the channel depth substantially in order to facilitate the massive ships of today to pass on through . . .

Port Phillip’s entrance is further complicated by a deep gorge that crosses the entrance which plummets to a depth of approximately 90 m – to these ingredients add massive ocean swells from Bass Strait and gale force winds – and you are left with a frightfully deadly cocktail.

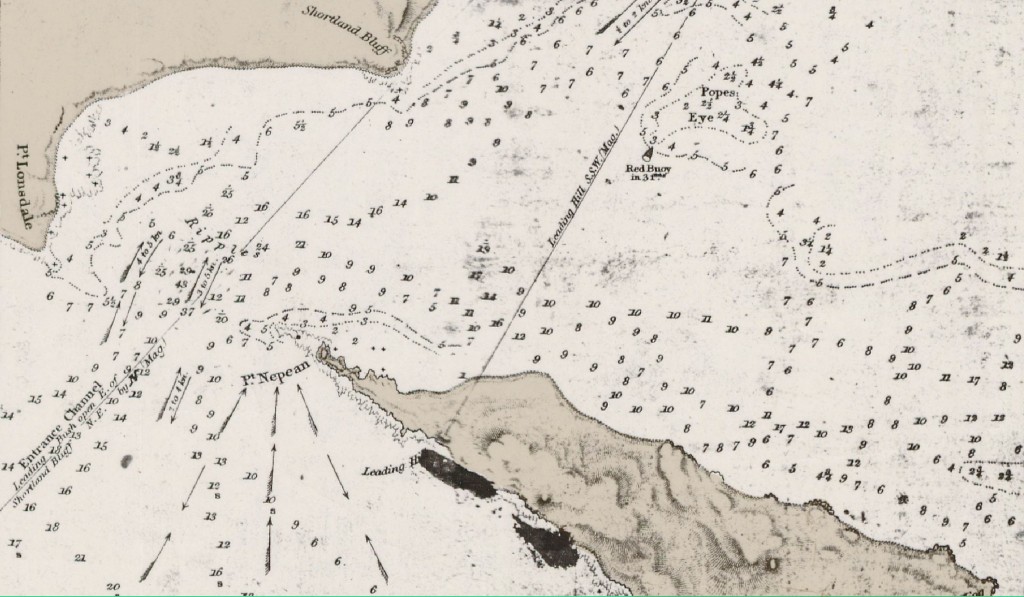

The ‘Lonsdale Reef’ can often be seen at low tide, projecting some 500 m across the entrance from Point Lonsdale, with rocky outcrops stretching out a further 200 m or so. The ‘Point Nepean Reef’, of which the notorious Corsair Rock is part of, extends from the eastern side of ‘The Rip’ extending outwards for some 700 m. The depth of the sea floor within ‘The Rip’ itself varies from a massive 48 fathoms [88 m] to less than 2 fathoms [3.5 m] amidst the rocky reefs and shoals as demonstrated in the Admiralty Chart extract below:

Extract – Admiralty Chart 1171 re Port Phillip by Commander IC Wickham in HMS Beagle c 1839 – Note measurements are in Fathoms

With reference to Chart 1171 above, ‘The Rip’ was described as:

” . . . The entrance to the bay is restricted in depth by two rocky banks of dune limestone. The 600 feet [183 m] wide main shipping channel passes over the outer Rip Bank and the inner Nepean Bank. This channel has been deepened by blasting, over the past 60 years, from a least depth of 30 feet [9 m] to its present declared minimum depth of 48 feet [14.5 m].

Between the two rocky banks lies a gorge with depths exceeding 300 feet [91 m], while south of Rip Bank the depths increase to approximately 90 feet [27.4 m] 1 mile [1.6 km] offshore.

The strong tidal flow through the very irregular constricted entrance produces the race, which is known as ” The Rip “.

Tides and Tidal Streams

Owing to the narrow entrance and the large area of Port Phillip Bay, the range of tides within the bay is small in comparison with that at the entrance. Although tidal ranges exceeding 5½ feet [1.7 m] do occur at Port Phillip Heads, the mean range normally varies from approximately 2½ feet [0.7 m] to 3½ feet [1.1 m]. At the northern end of the bay the tidal range normally varies from 1¼ feet [0.4 m] to 2 feet [0.6 m].

The in-coming flood tide streams through the entrance from the south and east. At high tide, under normal conditions, the flood tide may reach a maximum of about 6 knots as it passes through the Heads. It then turns and spreads out towards Shortland Bluff and Point King, before passing through the sand banks with diminished strength.

The out-going ebb tide sets towards the bight between Point Lonsdale and Shortland Bluff, and then out through the entrance and away south-eastward along the shore. Slack water occurs near mid-tide when the levels inside and outside the Heads are the same.

Extreme weather conditions can cause the level in the bay to be raised or lowered, and thus change the strength and duration of the tidal streams . . . “

Source: Excerpt – “Memoirs of the National Museum of Victoria”, No. 27 – issued 2nd November 1966 – J. McNally, Director

These elements together with severe weather squalls can result in a short stretch of sea that is amongst the most dangerous in the world. The sandy shoals just within the Heads that extend across from the western shores, eastward, provide yet another obstacle – it is so easy to understand the large number of ships that came to grief whilst attempting to negotiate this passage – especially during the period of the 19th century when sail was the only method of propulsion . . .

As the settlement of Melbourne rapidly expanded from the year 1835 onwards, especially with the discovery of gold in the 1850’s when Melbourne’s population literally exploded, the narrow passage presented innumerable problems for shipping. It is estimated that the treachery of ‘The Rip’ claimed some 200 ships.

On the 17th June 1839, the first Sea Pilot Licence was granted to George Tobin, by the New South Wales Governor, Gipps, on the proviso that ” . . . the appointment must not bring any expense on the Government . . . “ The pilots operated from Queenscliff, on the Bellarine Peninsula – using 30 ft (9.1 m) whaleboats to reach the ships. The service, though greatly advanced, continues to be vital to the safe navigation of the enormous ships that traverse ‘The Rip’ today.

The solution to this deadly stretch of water was to widen the entrance. The first blasting of various underwater rocky outcrops at the entrance of Port Phillip Bay, took place in the early 1880’s, and has continued until recent years . . .

Incredibly and miraculously, the first two recorded explorers to discover, map and document Port Phillip Bay, safely navigated this passage:

![]() both noted the incredibly narrow entrance, the tremendous fluctuations in depths, the fast flow of the tide through the passage, and, the rippling water that suggested erratic hazards not far below:

both noted the incredibly narrow entrance, the tremendous fluctuations in depths, the fast flow of the tide through the passage, and, the rippling water that suggested erratic hazards not far below:

.

January 1802 – Lieutenant John Murray & Crew on H.M. Survey Vessel ‘Lady Nelson’

Lieutenant John Murray sent a team into Port Phillip to determine a safe route for the ‘Lady Nelson’:

” . . . At 4 A.M.* (* It will be seen that Bowen left to explore Port Phillip at 4 A.M. of January 31st and not on February 1st.) I sent the launch with Mr. Bowen and 5 men armed with 14 days’ provisions and water down to the westward giving him particular instructions how to act both with respect to the harbour and natives should he fall in with any, the substance of which was that in finding a channel into the Port he would take marks proper for coming in with the vessel and immediately return to me and at all times to deal friendly with the natives. It may now be proper to observe that my intentions are that if a passage into that harbour is found I will take the vessel down into it and survey it as speedily as circumstances will allow, from that trace the coast to Cape Albany, from Cape Albany run strait to Cape Farewell and Harbinger Rocks, and if time, after that follow up the remainder of my orders . . . “

.

” . . . Saturday, February 13th. From 7 P.M. till 10 P.M. constant loud thunder, vivid lightning and very hard rain later part, till 9 A.M. Was calm then. A breeze sprung up at east. Hove up our B.* [* Bower, that is anchor.] and hung by the kedge, by this time it fell calm and our hopes of getting to sea vanished, needless to observe this kind of weather is as destructive to the intent of this cruise as gales at sea. I took a walk along the beach far enough to see all the entrances to this port and by ascending an eminence was confirmed in my opinion that several of those dangerous sand rollers had shifted their berths and by so doing had rendered the channel narrower than hithertofore.

“Sunday, February 14th…At 5 A.M. weighed and made all sail down the port, by 8 A.M. Grant’s Point bore east by north distant 10 miles and Cape Shanks north-west distant 7 miles; kept running down the land. A.M. At half-past 10 South Head of the new Harbour or Port north by east 8 miles distant; by noon the island at entrance of harbour bore north half a mile distant. At this time we had a view of this part of the spacious harbour, its entrance is wide enough to work any vessel in, but, in 10 fathoms. Bar stretches itself a good way across, and, with a strong tide out and wind in, the ripple is such as to cause a stranger to suspect rock or shoals ahead. We carried in with us water from 14 to 16 fathoms. Kept standing up the port with all sail set . . . “

“Monday, February 15th. P.M. Working up, the port with a very strong ebb against us, we however gained ground. The southern shore of this noble harbour is bold high land in general and not clothed as all the land at Western Point is with thick brush but with stout trees of various kinds and in some places falls nothing short, in beauty and appearance, of Greenwich Park . . . “

.

” . . . Thursday, March 11th. At 7 weighed and made sail down the port by 8 A.M. with a strong tide of ebb running out we got into the entrance carrying all the way from 9 to 16 fathoms water, we then fell into such a ripple that we expected every minute it would break on board–got clear and by half-past the point of entrance bore north-east by east 4 miles and a remarkably high nob of land (if not an island) west-north-west 4 or 5 miles, by noon the entrance north-east by west 9 or 10 miles . . . “

Source: Excerpts – “The Logbooks of the Lady Nelson” – by Ida Lee – Chapter 6 – published 1915

.

April 1802 – Matthew Flinders R.N. & Crew on H.M. Survey Sloop ‘Investigator’

Matthew Flinders and members of his crew thoroughly watched and observed this stretch of water before tackling it in the ‘Investgator’ – they deduced that they had to wait until the slack tide before attempting the passage. The following are extracts from the writings of Matthew Flinders about the entrance into the bay and of his first impressions of the “vast piece of water” (Port Phillip Bay) he encountered on Monday, April 26th 1802:.

.

” . . . In the morning we kept close to an east-south-east wind, steering for the land to the north-eastward; and at nine o’clock captain Grant’s Cape Schanck, the extreme of the preceding evening, was five leagues distant to the N. 88° E., and a rocky point towards the head of the bight bore N. 12° E. On coming within five miles of the shore at eleven o’clock we found it to be low, and mostly sandy, and that the bluff head which had been taken for the north end of an island was part of a ridge of hills rising at Cape Schanck. We then bore away westward in order to trace the land round the head of the deep bight; and a noon, the situation of the ship and principal bearings were as under:

Latitude observed, 38° 22′

Longitude by time keepers, 144 31½

Cape Schanck, S. 68° E.

The rocky point, distant 6 or 7 miles, N. 48 E.

Highest of two inland peaks, N. 15 W.

A squaretopped hill near the shore, N. 28 W.

Extr. of the high land towards C. Otway, S. 56 W.

On the west side of the rocky point there was a small opening, with breaking water across it; however, on advancing a little more westward the opening assumed a more interesting aspect, and I bore away to have a nearer view. A large extent of water presently became visible within side; and although the entrance seemed to be very narrow, and there were in it strong ripplings like breakers, I was induced to steer in at halfpast one, the ship being close upon a wind and every man ready for tacking at a moment’s warning. The soundings were irregular between 6 and 12 fathoms until we got four miles within the entrance, when they shoaled quick to 2¾. We then tacked; and having a strong tide in our favour, worked to the eastward between the shoal and the rocky point, with 12 fathoms for the deepest water. In making the last stretch from the shoal the depth diminished from 10 fathoms quickly to 3, and before the ship could come round, the flood tide set her upon a mud bank and she stuck fast. A boat was lowered down to sound, and finding the deep water lie to the northwest, a kedge anchor was carried out; and having got the ship’s head in that direction, the sails were filled and she drew off into 6 and 10 fathoms; and it being then dark, we came to an anchor.

The extensive harbour we had thus unexpectedly found I supposed must be Western Port, although the narrowness of the entrance did by no means correspond with the width given to it by Mr. Bass. It was the information of captain Baudin, who had coasted along from thence with fine weather, and had found no inlet of any kind, which induced this supposition; and the very great extent of the place, agreeing with that of Western Port, was in confirmation of it. This, however, was not Western Port, as we found next morning; and I congratulated myself on having made a new and useful discovery; but here again I was in error. This place, as I afterwards learned at Port Jackson, had been discovered ten weeks before by lieutenant John Murray, who had succeeded captain Grant in the command of the Lady Nelson. He had given it the name of PORT PHILLIP, and to the rocky point on the east side of the entrance that of Point Nepean . . . “

Source: Excerpt – “A Voyage to Terra Australis” – Volume I – by Matthew Flinders – Chapter 9 – published 1814

.

A safe passage would, however, not be the case for the many, many ships that have been damaged or totally wrecked whilst attempting to traverse ‘The Rip’ over the next 200+ years . . .

Helpful Hints:

Shortland’s Bluff

– Viewing Point from the Bellarine Peninsula located approximately 800 m South of the Queenscliff Town Centre

Point Lonsdale

– Viewing Point from the Bellarine Peninsula located approximately 750 m South of the Point Lonsdale Town Centre

Point Nepean

– Viewing Point from the Mornington Peninsula located approximately 6.5 km North-West of the Portsea Town Centre

– Located at the Western Extremity of Point Nepean National Park

– Parking at Gunners Cottage Car Park

Sorry, no records were found. Please adjust your search criteria and try again.

Sorry, unable to load the Maps API.