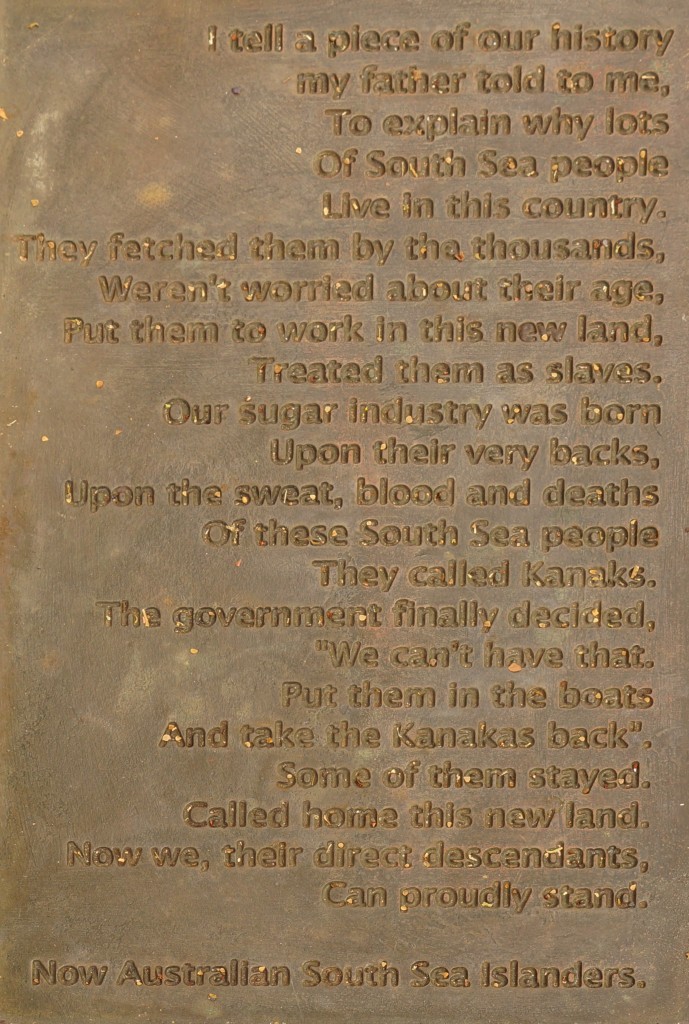

The importing of Polynesian labour (kanakas) began in Townsville, Queensland in 1863. Yes, Australia, sadly, took part in what can only be literally described as, ‘slavery’. What began as a recruitment drive from the South Sea Islands, with undoubtedly ‘honourable’ intentions, though always to be poorly paid, quickly succumbed to greed – involving the alleged kidnapping of these peoples from their island homes. It is estimated that over 60,000 Kanakas were ‘recruited’ until it became illegal to do so on the 31st December 1890. Many did not survive the treacherous journey to Australia, let alone white man’s diseases, exploitation, alchohol, gambling . . .

The mortality rate of Kanakas was some 5 to 6 times higher than that of a European.

The Kanakas were first used to work the cotton fields, however, as sugarcane developed into the leading and increasingly successful crop of the north-eastern reaches of Australia, the kanakas were soon migrated to work the cane fields:

” . . . When Robert Towns started cotton-growing on Townsvale plantation on the Logan River in 1863, there was a scarcity of white labour, and a serious doubt of the industry being able to pay white men’s wages. So Towns decided to import a lot of Polynesians from the South Sea Islands, and he engaged a man named Ross Lewin to take charge of the undertaking. Lewin had been years among some of the islands and knew the islanders, their customs and language, and he got the first sixty kanakas from the islands of Tanna, Malicolo, Erromanga, and Sandwich. Towns gave Lewin two documents, one an agreement to pay the islanders ten shillings per month, provide good food, good camps, and return to their islands in twelve months. The other was addressed to any mission, explaining the object of Lewin’s visit and offering a guarantee that the recruits would be properly cared for . . . “

.

” . . . In August, 1863, nearly four years after the establishment of responsible government, Captain Robert Towns landed from the schooner “Don Juan” the first consignment of kanakas . . . “

.

” . . . Polynesian labour grew into a vast and flourishing system, until the sugar lands of the North practically produced their crops wholly by its aid. The advent of this, perhaps, the least objectionable class of black labour, in time led, as it undoubtedly did, to the division of political parties, to bitter political strife, to acute personal differences among our leading politicians, to numerous social evils of varying kinds, and to the shocking tragedy of murder, raping, kidnapping, and all the violence attendant upon all forms of black slavery. So large a part did this trade play in legislation and administration, extending over a long period of years, that the subject could not be overlooked in the political history of the State. The whole trade was a blight upon our social and political life, yet the kanaka was a peaceable, law-abiding, kindly disposed savage, responsive to any act of benevolence, suited to the work for which he was imported, moderately industrious, faithful to those who gained his confidence, and with no particular ambitions in regard to inter-marriage with the white race. The was the early kanaka . . . “

.

” . . . In 1868 Governor Blemore, of New South Wales, reported complaints against the recruiting on the islands, and in February of that year he received a petition, signed by eight missionaries, praying for an enquiry into the manner in which natives were being recruited in the New Hebrides. This petition contained serious charges, and a unanimous opinion that the system of obtaining Polynesian labour recall the worst days of the slave trade . . . “

Excerpt: “The History of Queensland: Its People and Industries” by Matt. J. Fox – pp 684 – published 1923

.

Hence, the government responded by creating a ‘Bill to Regulate and Control the Introduction and Treatment of Polynesian Laborers’. Bill No. 47 was assented to on the on the 4th March 1868. The preamble read:

“WHEREAS many persons have deemed it desirable and necessary in order to enable them to carry on their operations in tropical and semi-tropical agriculture to introduce to the colony Polynesian laborers And whereas it is necessary for the prevention of abuses and for securing the laborers proper treatment and protection as well as for securing to the employer the due fulfilment by the immigrant of his agreement that an Act should be passed for the control of such immigration Be it therefore enacted by the Queen’s Most Excellent Majesty by and with the advice and consent of the Legislative Council and Legislative Assembly of Queensland in Parliament assembled and by the authority of the same as follows – . . . “

Source: Excerpt – ‘Polynesian Laborers Bill’ – assented to on the 4th March 1868

The Bill was very detailed, including forms, for example :

Application to introduce South Sea Island labourers

A form declaring that no kidnapping had transpired

A license to recruit the labourers

A ‘Memorandum of Agreement’ – which included daily food rations, annual clothing rations

Each Plantation had to maintain a register of islanders ’employed’

A form for the transfers of labourers

A declaration that the labourers would be returned to their native islands after 3 years or ” . . . thirty-nine moons from the date of arrival . . . “

.

The work in the cane fields was hard. Though white man was perfectly capable in working the fields, they were not to be convinced into working such long and intense hours in the heat and humidity of north-eastern Australia, for such a meagre pay:

” . . . The white labour of plantations is skilled and the line of demarcation between it and the kanaka seen, and the drudgery of the canefields devolving on the latter. Form observation there seems no reason why white men should not perform all the labour on the canefields . . . “

Excerpt: “The History of Maryborough & Wide Bay & Burnett Districts” by George E. Loyau – published 1897 – pp 368

.

The ‘Warwick Argus’ (Qld) published an article on the Pacific Island Labourers Act of 1880 – on the 22nd April 1884.

Initially, the legislation proved ineffective in kerbing the greed and manipulation of the early cane growers:

” . . . In the meantime, however, information gradually began to leak out with regard to the transactions of those in charge of certain vessels, which left the Queensland coast during 1884. Those vessels were the “Hopeful,” “Ceara,” “Lizzie,” “Sybil,” “Forest King,” and “Heath.” The Government appointed a commission to investigate the charges made, and they carried out their inquiries on the spot, in addition to examining 500 islands in Queensland, and the conclusion of the commissioners was that none of the islanders understood the nature of their engagements . . . ‘

.

” . . . Act relating to Pacific Island labour was passed by Samuel Griffith in November, 1885. The eleventh and last section of this Act provided: –

“After the thirty-first day of December, One thousand eight hundred and ninety, no licence to introduce Islanders shall be granted.” . . . “

Excerpt: “The History of Queensland: Its People and Industries” by Matt. J. Fox – pp 686 – published 1923

.

The ignominy of slave labour in Australia lead to the passing of no less than 23 Acts, including Amendment Acts, between the years 1872 to 1912 – the most recorded in any one industry up to 1923 . . .

The cessation of licences caused much controversy amidgst the sugarcane industry. The cane growers were granted five years notice – which would seem a generous length of time to modify their labour requirements. In fact, the importation of kanakas had to cease by the December of 1890. This meant that the islanders brought in up to that date, would each be on the allowable 3 year contract – essentially equating to the sugar industry having up to 8 years in which to organise their labour resources.

Even so, many sugar producers did not survive the loss of their cheap labour . . .

As has been proven throughout history, change can bring about spurts of innovation, which is exactly what happened to the sugar industry. Design, trial, error, inventiveness and resourcefulness created machinery to take over this labour intensive industry.

Further Reading: Chapter “Kanaka Labour” – “The History of Queensland: Its People and Industries” by Matt. J. Fox – c 1923

.

View other important events in Queensland’s History . . .