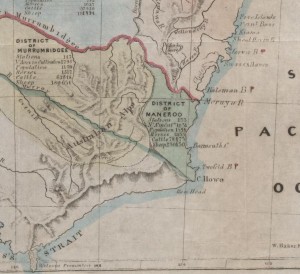

The ‘Maneroo’ was the early reference to what is now known as the most southern coastal region of New South Wales.

Angus McMillan’s first expedition southward, to the district now known as Gippsland, commenced on the 20th May 1839.

McMillan describes his voyage of discovery through the lands to the south-westward of Maneroo in the following transcript of a letter written in response to a circular letter from His Excellency Lieutenant-Governor La Trobe, addressed to a number of the remaining early settlers (noting that many had already passed away by this time), requesting information as to the time and circumstances of the first occupation of various parts of the colony of Victoria, Australia; dated the 29th July 1853:

MEMORANDUM OF TRIP BY A. MCMILLAN, FROM MANEROO DISTRICT, IN THE YEAR 1839, TO THE SOUTH-WEST OF THAT DISTRICT, TOWARDS THE SEA-COAST, IN SEARCH OF NEW COUNTRY.

Start from Maneroo.

On the 20th of May 1839, I left Currawang, a station of James McFarlane, Esq., J.P., of the Maneroo district, having heard from the natives of that district that a fine country existed near the sea-coast, to the south-west of Maneroo.

Accompanied by one Black only. I was accompanied in my expedition by Jemmy Gibber, the chief of the Maneroo tribe.

After five days’ journey towards the south-west, I obtained a view of the sea from the top of a mountain, near a hill known as the Haystack, in the Buchan district, and also of the low country towards Wilson’s Promontory.

On the sixth day after leaving Currawang the blackfellow who accompanied me became so frightened of the Warrigals, or wild blacks, that he tried to leave me, and refused to proceed any further towards the new country. We pressed on until the evening, when we camped, and about twelve o’clock at night I woke up, and found Jemmy Gibber in the act of raising his waddy or club to strike me, as he fancied that, if he succeeded in killing me, he would then be able to get back to Maneroo. I presented a pistol at him, and he begged me not to shoot him, and excused himself by saying that he had dreamt that another blackfellow was taking away his gin, and that he did not mean to kill me.

Omeo.

Next morning we started for Omeo, where we arrived after four days’ journey over very broken country. There were three settlers at Omeo at this time, viz., Fender, McFarlane, and Hyland.

Numbla-Munjee.

On the 16th September 1839 I formed a cattle station at a place called Numbla-Munjee, on the River Tambo, 50 miles to the south of Omeo, for Lachlan Macalister, Esq., J.P. A Mr. Buckley had, previous to my arrival here, formed a station ten miles higher up the River Tambo from Numbie-Munjee.

On the 26th of December 1839 I formed a party, consisting of Mr. Cameron, Mr. Matthew Macalister, Edward Bath, a stockman, and myself, with the view of proceeding towards and exploring the low country I had formerly obtained a view of from the mountain in the Buchan district alluded to in my first trip from Maneroo. After travelling for three days over a hilly and broken country, one of our horses met with a serious accident, tumbling down the side of one of the steep ranges, and staked itself in four or five places. In consequence of this accident we were compelled to return to Numbla-Munjee.

On the 11th of January 1840, the same party as before, with the addition of two Omeo blacks Cobbon Johnny and Boy Friday started once more with the same object in view, namely, that of reaching the new country to the south-west, and, if possible, to penetrate as far as Corner Inlet, where I was led to believe there existed an excellent harbour.

Meet with the Aborigines. After a fearful journey of four days, over some of the worst description of country I ever saw, we succeeded in crossing the coast range leading down into the IOAV country. This day we were met by a tribe of the wild blacks who came up quite close to us, and staved at us while on horseback, but the moment I dismounted they commenced yelling out, and took to their heels, running away as fast as possible; and from the astonishment displayed at the circumstance of my dismounting from the horse, I fancied they took both man and horse to constitute one animal.

Lake Victoria.

On Wednesday, the 15th of January, our little party encamped on the River Tambo, running towards the sea in a south-easterly direction. On the morning of the 16th we started down the Tambo, in order, if possible, to get a sight of a lake we had previously seen when descending the ranges to the low country and which I was certain must be in our immediate vicinity. The country passed through to-day consisted of open forest, well grassed, the timber consisting chiefly of red and white gum, box, he- and she-oak, and occasionally wattle. At six p.m. we made the lake, to which I gave the name of Lake Victoria. From the appearance of this beautiful sheet of water, I should say that it is fully 20 miles in length and about 8 miles in width. On the north side of this lake the country consists of beautiful open forest, and the grass was up to our stirrup-irons as we rode along, and was absolutely swarming with kangaroos and emus. The lake was covered with wild ducks, swans, and pelicans. We used some of the lake water for tea, but found it quite brackish. We remained on the margin of the lake all night. The River Tambo was about one mile north-east of our camp. The River Tambo, where we first made it, appears to be very deep and from 20 to 30 yards wide. The water is brackish for the distance of about five miles from its mouth, where it empties itself into Lake Victoria.

Nicholson River.

On the 17th January, started from the camp, and proceeded in a south-westerly direction. At ten a.m. came upon another river, to which I gave the name of the Nicholson, after Dr. Nicholson, of Sydney. This river seemed to be quite as large as the Tambo, and as deep. Finding we were not able to cross it in the low country, we made for the ranges, where, after encountering great difficulties, we succeeded in crossing it but not until sun-down high up in the ranges, and encamped for the night. This evening we found that, from the great heat of the weather, our small supply of meat had been quite destroyed. We were, however, fortunate enough to obtain some wild ducks, upon which we made an excellent supper.

River Mitchell 18th January.

Started again upon our usual course (south-west), and, after travelling about seven miles, came upon a large river, which I named the Mitchell, after Sir Thomas Mitchell, Surveyor-General of New South Wales.

Clifton’s Morass.

We followed this river up until we came to a large morass, to which I gave the name of Clifton’s Morass, from the circumstance of my having nearly lost in it, from its boggy nature, my favourite horse Clifton.

General View of Country from a Hill.

Having crossed this morass, we again proceeded on our journey for three miles, when we came once more upon the Mitchell River higher up, and encamped for the night, the country improving at every step. In the evening I ascended a hill near the camp, from the top of which I obtained a good view of the low country still before us, of the high mountains to the north-west, and the lakes stretching towards the sea-coast in a south and south-easterly direction; and, from the general view of the country as I then stood, it put me more in mind of the scenery of Scotland than any other country I had hitherto seen, and therefore I named it at the moment “Caledonia Australia”.

On the morning of the 19th January we crossed the Mitchell, and proceeded in a south- south-west course, through fine open forest of she-oak and red and white gum, for about sixteen miles, and encamped upon a chain of ponds in the evening.

20th January.

We proceeded in a south-west course, and at ten a.m. came upon the border of a large lake, which I believed to be a continuation of the same lake we had been previously encamped upon.

The Aborigines.

While at dinner on the banks of the lake a tribe of blacks were walking quietly up to where we were encamped, but as soon as they saw us on horseback they left their rugs and spears and ran away. They never would make friends with us upon any occasion.

The River Avon. 21st January.

Started upon our usual course (south-west), and, after travelling about four miles, came upon a river flowing through a fine country of fine, open forest, with high banks, to which I gave the name of the Avon. We followed this river up all day, and crossed it about twenty miles from the foot of the mountains. It appears to be a mountain stream, generally not very deep, and runs over a bed of shingle. The country around and beyond the place where we crossed the Avon consists of beautiful, rich, open plains, and appeared, as far as I could judge at the time, to extend as far as the mountains. We encamped upon these plains for the night. From our encampment we had a splendid view of the mountains, the highest of which I named Mount Wellington, and also I named several others, which appear in the Government maps (published) of Gippsland.

22nd January.

Left the encampment on the plains, and proceeded on our usual course of south-west, and travelled over a beautiful country, consisting of fine, open plains, intersected by occasional narrow belts of open forest, extending as far as the lakes to the eastward and stretching away west and north-west as far as the foot of the mountains.

Macalister River.

After travelling about ten miles we encamped in the evening on a large stream, which I named the Macalister. This river appears deep and rapid, and is about 40 yards wide. Here we saw an immense number of fires of the natives.

23rd January.

Started early in the morning, and tried to cross the river, but could not succeed, and followed the River Macalister down to its junction with another very large river called the La Trobe, which river is bounded on both sides by large morasses.

Meet with Aborigines.

In the morass to north-east of the river we saw some 100 natives, who, upon our approach, burnt their camps and took to the scrub. We managed to overtake one old man that could not walk, to whom I gave a knife and a pair of trousers, and endeavoured by every means in our power to open a communication with the other blacks, but without success.

It was amusing to see the old man. After having shaken hands with us all, he thought it necessary to go through the same form with the horses, and shook the bridles very heartily. The only ornaments he wore were three hands of men and women, beautifully dried and preserved. We were busy all the evening endeavouring to cut a bark canoe, but did not succeed.

On the morning of the 24th January, the provisions having become very short, and as some of the party were unwilling to prosecute the journey upon small allowance, I determined upon returning to the station and bringing down stock to the district. We then returned to Numbla-Muujee, which place we made in seven days from the 24th, and were the last two days without any provisions at all.

I may add that I was the first person who discovered Gippsland, and when I started to explore that district I had no guide but my pocket compass and a chart of Captain Flinders. We had not even a tent, but used to camp out and make rough gunyahs wherever we remained for the night.

On the 27th March 1840, Count Strzelecki and party left our station at Numbla-Munjee for Caledonia Australis. He was supplied with some provisions and a camp kettle, and Mr. Matthew Macalister, who was one of my party in January of the same year, accompanied them one day’s journey, and, after explaining the situation and nature of the country about the different crossing places, left them upon my tracks on the coast range leading to Gippsland, and which tracks Charley, the Sydney blackfellow, who accompanied Count Strzelecki, said he could easily follow.

On my return to Numbla-Munjee on the 31st January, after having discovered the country of Gippsland as far as the La Trobe River, I proceeded immediately to Maneroo, and reported my discovery to Mr. Macalister, who did not publish my report at the time. I had also written another letter to a friend of mine in Sydney, containing a description of my expedition; at the same time I wrote to Mr. Macalister, but it unfortunately miscarried.

In October 1840 I arrived in Gippsland with 500 head of cattle, and formed a station on the Avon River, after having been six weeks engaged in clearing a road over the mountains.

After four attempts I succeeded in discovering the present shipping place at Port Albert, and marked a road from thence to Numbla-Munjee, a distance of 130 miles.

After having brought stock into the district, and formed the station in about the month of November 1840, the aborigines attacked the station, drove the men from the hut, and took everything from them, compelling them to retreat back upon Numbla-Muujee.

On the 22nd December 1840, I again came down and took possession of the station, when the natives made a second attack.

.

A. MCMILLAN.

View other important information on Discovering Terra Australis . . .

View other important events in this Region’s History . . .

View other important events in Victoria’s History . . .